John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), for those of us who didn't take economics (or who tried and failed) was the great British sage who, in addition to helping found modern macroeconomics, advocated government intervention to ease economic disruption. Keynesian economic theories were hot for much of the second half of the twentieth century but fell out of fashion in the 1980s. With the current economic crisis, Keynes is back. One of Keynes' notions is the “paradox of thrift.” Common wisdom tells us it is good to save for the future, but what makes sense for individuals may not be good for the economy as a whole, hence the paradox. What's true of the parts may not be equally true for the whole—and that's what Keynes argued—while saving for a rainy day is good for you, if everyone is saving then no one is spending and that hurts everyone.

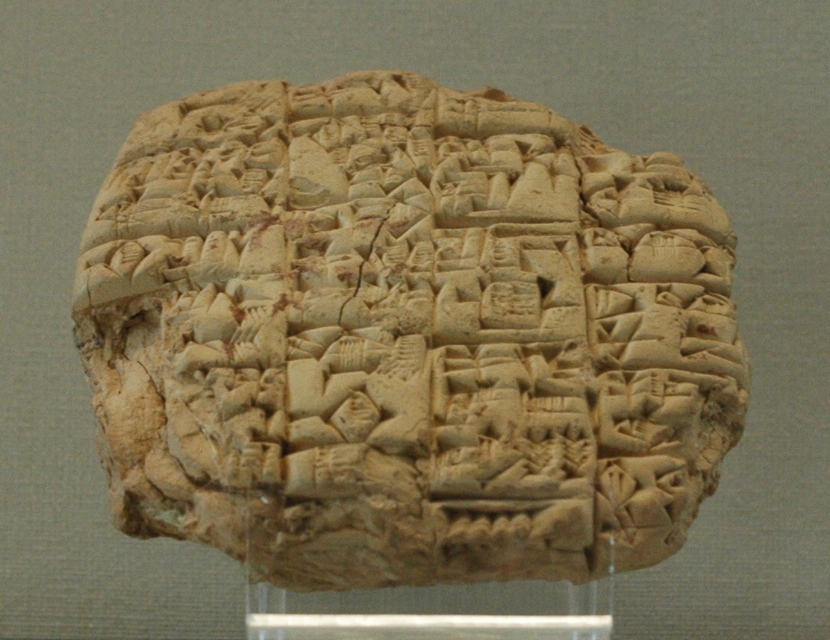

Which brings me to my second favorite economist—Joseph. No, not Joseph Stiglitz (also a Keynesian), Joseph from the Hebrew Bible. As you recall, Joseph was sold into bondage in Egypt by his brothers who were jealous of his standing with their father, Jacob. Joseph rose to prominence in Pharaoh's court because of his ability to interpret dreams. In Genesis 41 we read that Pharaoh dreamed he saw seven fat cows come up from the Nile followed by seven skinny cows; the skinny cows devoured the fat ones. Then he dreamed of seven healthy heads of grain and seven thin heads of grain and the thin stalks devoured the healthy ones. The dreams' meaning confounds the wise men of Egypt but Joseph accurately predicts that the dream foretells seven good years followed by seven bad years. He advises Pharaoh to put aside in local government granaries 1/5 of the surplus in the good years to alleviate suffering in the bad times ahead. Joseph was Keynes before Keynes was Keynes.

So what does this all have to do with marketing? As the economy contracts, many businesses, whether out of panic or financial necessity, begin to make across-the-board cuts. Marketing, the engine that drives brand awareness, sales opportunities, and market share, suffers as a result. The “Jospehians” among us undoubtedly put aside tidy sums during the past boom so they needn't read any further, but, like I said, people are funny. In the off chance that you were not as foresighted as Joseph, what should you do? If you are a Wall Street billionaire, don't worry, you'll either be bailed out or go to prison. Either way your daily needs will be met. And, frankly, living on one's remaining millions requires fewer sacrifices than one might imagine. Car manufacturers probably won't have it so easy and they may have to learn German or Japanese to survive. Small and medium-sized business will be even less lucky and will have to make tough marketing choices.

So where should you spend your marketing dollars? Here are three things to keep in mind:

- Targeted marketing gets better response. The more relevant the content the better the return on investment.

- Use resources like client databases, web analytics, and surveys to consistently craft more relevant campaigns.

- Figure out who your best customers are and market to them often.